A little over two decades ago popular culture was all of a sudden immersed in the idea that reality might not be so real after all. The Matrix, Dark City and The Truman Show all looked at this idea from different angles, though it was The Matrix that most explicitly transmitted the idea of ‘Simulation Theory’: that the world we think of as ‘reality’ might in fact be a computer simulation, with us inserted into avatars within that simulation with no memory of our prior existence.

More than two decades prior to that though, science fiction legend Philip K. Dick – whose works would go on to be adapted into many movies: Blade Runner, Total Recall, Minority Report, The Adjustment Bureau and others – was already exploring the concept of parallel and nested realities (both in his novels, and in his own life). His famous 1977 lecture in France gave rise to the idea that déjà vu might be a glitch in our computer-programmed simulation – ‘a glitch in the Matrix’ – and now serves as the title, and thematic backbone, of a new documentary from Rodney Ascher (The Nightmare, Room 237).

Ascher’s A Glitch in the Matrix isn’t just simply a look at the idea of the Simulation Hypothesis though. It is, more significantly, a look at how that idea affects humans themselves, and on a larger scale, what its acceptance might mean for society. Those who have watched Ascher’s previous documentaries will not be surprised by this, as they too have looked at strange ideas/phenomenon through the prism of their effect on those who become entangled with them.

The documentary is divided into seven parts, with various elements of PKD’s 1977 lecture introducing each and thus serving as the axle around which the various facets of the A Glitch in the Matrix revolve:

- Variables: Four eyewitnesses

- Revelations: Seeing the code

- The Kingdom of G*d: Notes towards a digital theology

- Other People: I know I am, but what are you?

- Matrixes and Matrices: Antecedents, impacts, and unexpected consequences of a certain major motion picture.

- The Real World: But which one?

- Conclusions: (Where applicable)

Those ideas are explored in A Glitch in the Matrix through interviews with the ‘four eyewitnesses’ mentioned in the title of the first section, as well as a number of experts including Simulation Theory superstar Nick Bostrom and author Erik Davis (Techgnosis: Myth, Magic and Mysticism in the Age of Information).

The first section introduces the overall idea that we might be living in a computer-generation simulation, and also to the four ‘eyewitnesses’…kind of: we don’t see the ‘real’ people, instead they are always represented by computer generated avatars. A neat way of relating to the subject matter, for sure, although some might perhaps feel that the interviews lose their gravity when shown in this manner. However, right off the bat, one of the eyewitnesses says something fairly profound (that isn’t explored a whole lot further in the documentary though):

I was in a class when I was in college…in the early ’90s. And a teacher was in front of the class, and the teacher said: ‘Something interesting about the brain is that we actually can map what we think about the human nervous system by the highest level of technology of the day. So, for example, when the aquaducts were big, people thought that humors controlled the body – different liquids would come in and make you feel a different way. And then when the telegraph came, then all of a sudden we thought that these were nerve impulses going down sort of wires.’

And then she said, ‘now we know that the brain is a computer’. And I raised my hand, and I said ‘because that’s our highest level of technology’. And she said ‘no, the brain is a computer’.

The eyewitness’s point is that seeing a Simulation in terms of modern virtual reality (VR) technology “is something that we can use as a model, but it isn’t necessarily what is going on…we can use it, but we aren’t necessarily in a server room somewhere – it might be something different.” But we always see ourselves as being at the pinnacle of the evolution of technology, leading to a blind spot.

As such, they add as a caveat, “everything I’ve described here, keep in mind I’m a 21st century guy, that’s how my brain works – if you’re watching this in the future, we’re not dumb, we just don’t have the tools that you have to think of this stuff.”

Section two moves from the idea that we could be living in a simulation, to the effect that idea has on people. As with other sections, this is first channeled through PKD, namely his own ‘revelation’ in 1974 (after being administered sodium pentethol for dental surgery). “Some people claim to remember past lives,” PKD says in the replayed segment of his 1977 lecture in France. “I claim to remember a very different present life.”

The documentary then reveals the ‘conversion experiences’ of the four eyewitnesses, how they also came to believe that the world around them might just be a simulation. Viewers with a fairly skeptical or grounded approach to weird topics might at this point feel like these accounts are more evidence of possible mental disorders than a simulation…and they should perhaps hold on to that thought.

Section three moves on from the initial revelations/conversion experiences to exploring the belief/theological system that arises from it. Again PKD’s own thoughts are shared, as well as historical examples of Hindu myths about living in dreams within dreams, Plato’s allegory of the cave, Descartes’ philosophical ‘malicious demon’, the more modern scientific ‘brain in a vat’ model, and even our general conception of ‘heaven’ (eyewitness Gude notes that “the concept of people standing at the Pearly Gates, and looking at their lives – what is that if not a debrief, if you will, after you get out of a simulation?”).

It is in the fourth section (‘Other People: I know I am, but what are you?’) where things suddenly take a darker turn, as it asks what happens when contempating these ideas turns into a pathology; when the belief that this world is not actually the true reality inspires people to transgress societal and moral boundaries?

This is chiefly told through the implication that if you are immersed in a Simulation, then it is quite possible that – as in computer games – all the people around you are ‘NPCs’: non-playing characters, or automatons of a kind.

Here the visuals alone would be enough to get the message across: Ascher shows in-game video of people wantonly killing scores of other characters around them in various horrific ways. But when he does so as an overlay to audio of his interviews with the ‘eyewitnesses’ describing how they started seeing people around them as NPCs, the effect is disturbing. The point is made when ‘expert’ interviewee, Emily Pothast, then notes that the video of the 2019 New Zealand massacre was extremely similar, with its FPS viewpoint of indiscriminate killing of what the murderer viewed as NPCs.

Section five of the documentary extends on this by first noting the growth of belief in the idea of parallel realities/the Simulation idea: “PKD might have been surprised to learn how common ‘memories of a different present’ would be come in the 21st century”, the narrator notes (see Mike Jay’s “From mind control to The Truman Show: How paranoid delusions colonized popular culture” for more on this). Ascher mentions the rise in the popularity of the ‘Mandela Effect’ on internet messageboards, and continues exploring the beliefs of the four eyewitnesses (e.g. eyewitness Levine notes his implausible escape/survival from a car accident in Mexico: “Somebody’s gotta be putting their hand on the scale…the algorithm [is] tweaking probabilities to make it more interesting, because it’s a game.”). And we are then introduced to a fifth ‘eyewitness’ – Joshua Cooke – without the zany avatar or any explanation of his background, just an emotionless voice over the phone describing how he grew to become obsessed with The Matrix

The penultimate section of A Glitch in the Matrix begins innocently enough with discussion of crossovers between fiction and the ‘real world’, first by noting PKD’s own experience of this type before noting other examples, such as that of cartoonist Chris Ware. “There is something where you get into this imaginary world of writing stories and reimagining memories,” Ware says, “where you can kind of start to feel like you’re – not necessarily predicting the world – but having some play in the stream of it or something” (for more on this, see “Meeting their makers: The strange phenomenon of fictional characters turning up in real life“).

But then it returns to Cooke’s story, and the dangers of the idea that we are surrounded by NPCs is made horribly manifest. (Warning: there is first person narration in this section of the documentary – in a very dispassionate voice – of truly terrible violence. “It wasn’t anything like I had seen on The Matrix. Real life was so much more horrific.”).

As Erik Davis notes, one of the problems with Simulation theory is of seeing other worlds as Utopian or an escape, whereas Philip K. Dick “was always aware of the broken: people are broken, technologies are broken, cosmologies are broken, gods are broken.”

The conclusion of the documentary looks at how the awful crime narrated in the previous section came from a state of delusion. And then also another of the eyewitnesses (Gude) – thus far only shown as describing his revelation of the world as a simulation and other people as NPCs – also is allowed to tell of another, growing revelation as he has got older:

Now that I’m in my mid-40s I am actually finally able to deal with people as human beings. And you could think of it one way, if people are simulated: they’re getting better, and they’re easier to relate to. But is it possible that I saw everyone as these robotic humans walking around because *I* couldn’t figure them out, because of a problem with *my* brain?

It’s an extremely important lesson to share, though this darker theme throughout the second half of the documentary perhaps ends up overwhelming the overall topic, which to me is a fascinating one that could have been explored further in interviews with other experts. But, as previously noted, Ascher’s oeuvre is predominantly weighted towards exploring the human effect – and the most easily told stories in this topic likely skew dark.

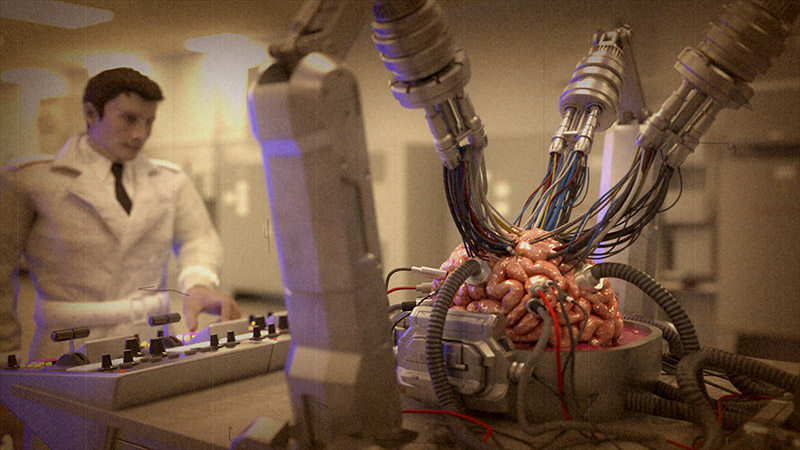

Overall, however, A Glitch in the Matrix presents a fascinating exploration of the Simulation topic, told through human ‘experiencers’ (PKD and the ‘eyewitnesses’). The visuals are well-crafted, from the many call-outs to movies on this subject area (Dark City, The Truman Show, The Wizard of Oz, The Adjustment Bureau and so on) used to illustrate ideas, through to the use of CG environments and avatars. Some criticism could perhaps be raised at the lack of female interviewees (Emily Pothast being the only one), and also of the clunky start-of-section ‘computer voice’ narration and font.

But beyond those minor critiques, it’s a documentary well worth checking out for anyone who, as Erik Davis says, has that “fundamental hunch that we all have” that we might one day wake from a dream within a dream.

A Glitch in the Matrix is available to watch at home via most streaming services – see the official website for links.